Although MERS-CoV has been shown to antagonize endogenous interferon (IFN) production, treatment with exogenous types I and III IFN (IFN-α and IFN-λ, respectively) have effectively reduced viral replication in vitro. When rhesus macaques were given interferon-α2b and ribavirin and exposed to MERS, they developed less pneumonia than control animals.Five critically ill people with MERS in Saudi Arabia with ARDS and on ventilators were given interferon-α2b and ribavirin but all ended up dying of the disease. The treatment was started late in their disease (a mean of 19 days after hospital admission) and they had already failed trials of steroids so it remains to be seen whether it may have benefit earlier in the course of disease. Another proposed therapy is inhibition of viral protease or kinase enzymes. Researchers are investigating a number of ways to combat the outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, including using interferon, chloroquine, chlorpromazine, loperamide, and lopinavir, as well as other agents such as mycophenolic acid and camostat.

In humans, common symptoms of influenza infection are fever, sore throat, muscle pains, severe headache, coughing, and weakness and fatigue. In more serious cases, influenza causes pneumonia, which can be fatal, particularly in young children and the elderly. Sometimes confused with the common cold, influenza is a much more severe disease and is caused by a different type of virus.

Saturday, September 5, 2015

Laboratory testing

MERS cases have been reported to have low white blood cell count, and in particular low lymphocytes.

For PCR testing, the WHO recommends obtaining samples from the lower respiratory tract via bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), sputum sample or tracheal aspirate as these have the highest viral loads.There have also been studies utilizing upper respiratory sampling via nasopharyngeal swab.

Several highly sensitive, confirmatory real-time RT-PCR assays exist for rapid identification of MERS-CoV from patient-derived samples. These assays attempt to amplify upE (targets elements upstream of the E gene),open reading frame 1B (targets the ORF1b gene)and open reading frame 1A (targets the ORF1a gene). The WHO recommends the upE target for screening assays as it is highly sensitive. In addition, hemi-nested sequencing amplicons targeting RdRp (present in all

coronaviruses) and nucleocapsid (N) gene (specific to MERS-CoV) fragments can be generated for confirmation via sequencing. Reports of potential polymorphisms in the N gene between isolates highlight the necessity for sequence-based characterization.

The WHO recommended testing algorithm is to start with an upE RT-PCR and if positive confirm with ORF 1A assay or RdRp or N gene sequence assay for confirmation. If both an upE and secondary assay are positive it is considered a confirmed case.

Protocols for biologically safe immunofluorescence assays (IFA) have also been developed; however, antibodies against betacoronaviruses are known to cross-react within the genus. This effectively limits their use to confirmatory applications. A more specific protein-microarray based assay has also been developed that did not show any cross-reactivity against population samples and serum known to be positive for other betacoronaviruses. Due to the limited validation done so far with serological assays, WHO guidance is that "cases where the testing laboratory has reported positive serological test results in the absence of PCR testing or sequencing, are considered probable cases of MERS-CoV infection, if they meet the other conditions of that case definition

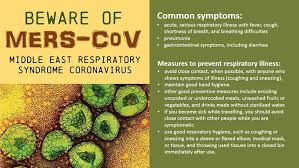

Prevention

While the mechanism of spread of MERS-CoV is currently not known, based on experience with prior coronaviruses, such as SARS, the WHO currently recommends that all individuals coming into contact with MERS suspects should (in addition to standard precautions):

- Wear a medical mask

- Wear eye protection (i.e. goggles or a face shield)

- Wear a clean, non sterile, long sleeved gown; and gloves (some procedures may require sterile gloves)

- Perform hand hygiene before and after contact with the person and his or her surroundings and immediately after removal of personal protective equipment (PPE)

For procedures which carry a risk of aerosolization, such as intubation, the WHO recommends that care providers also:

- Wear a particulate respirator and, when putting on a disposable particulate respirator, always check the seal

- Wear eye protection (i.e. goggles or a face shield)

- Wear a clean, non-sterile, long-sleeved gown and gloves (some of these procedures require sterile gloves)

- Wear an impermeable apron for some procedures with expected high fluid volumes that might penetrate the gown

- Perform procedures in an adequately ventilated room; i.e. minimum of 6 to 12 air changes per hour in facilities with a mechanically ventilated room and at least 60 liters/second/patient in facilities with natural ventilation

- Limit the number of persons present in the room to the absolute minimum required for the person’s care and support

- Perform hand hygiene before and after contact with the person and his or her surroundings and after PPE removal.

The duration of infectivity is also unknown so it is unclear how long people must be isolated, but current recommendations are for 24 hours after resolution of symptoms. In the SARS outbreak the virus was not cultured from people after the resolution of their symptoms.

It is believed that the existing SARS research may provide a useful template for developing vaccines and therapeutics against a MERS-CoV infection. Vaccine candidates are currently awaiting clinical trials.

Friday, September 4, 2015

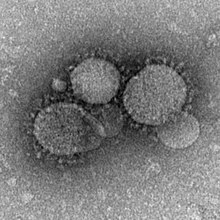

Betacoronavirus

Betacoronaviruses are one of four genera of coronaviruses of the subfamily Coronavirinae in the family Coronaviridae, of the orderNidovirales. They are enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses

of zoonotic origin. The coronavirus genera are each composed of varying viral lineages with the betacoronavirus genus containing four such lineages.

The Beta-CoVs of the greatest clinical importance concerning humans are OC43, and HKU1 of the A lineage, SARS-CoV of the B lineage, and MERS-CoV of the C lineage. MERS-CoV is the first betacoronavirus belonging to lineage C that is known to infect humans.

Natural reservoir

Early research suggested the virus is related to one found in the Egyptian tomb bat. In September 2012 Ron Fouchier speculated that the virus might have originated in bats.Work by epidemiologist Ian Lipkin of Columbia University in New York showed that the virus isolated from a bat looked to be a match to the virus found in humans.2c betacoronaviruses were detected in Nycteris bats in Ghana and Pipistrellus bats in Europe that are phylogenetically related to the MERS-CoV virus.

Recent work links camels to the virus. An ahead-of-print dispatch for the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases records research showing the coronavirus infection in dromedary camel calves and adults, 99.9% matching to the genomes of human clade B MERS-CoV.

At least one person who has fallen sick with MERS was known to have come into contact with camels or recently drank camel milk.

On 9 August 2013, a report in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases showed that 50 out of 50 (100%) blood serum from Omani camels and 15 of 105 (14%) from Spanish camels had protein-specific antibodies against the MERS-CoV spike protein. Blood serum from European sheep, goats, cattle, and other camelids had no such antibodies.]Countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates produce and consume large amounts of camel meat. The possibility exists that African or Australian bats harbor the virus and transmit it to camels. Imported camels from these regions might have carried the virus to the Middle East.

In 2013 MERS-CoV was identified in three members of a dromedary camel herd held in a Qatar barn, which was linked to two confirmed human cases who have since recovered. The presence of MERS-CoV in the camels was confirmed by the National Institute of Public Health and Environment (RIVM) of the Ministry of Health and the Erasmus Medical Center (WHO Collaborating Center), the Netherlands. None of the camels showed any sign of disease when the samples were collected. The Qatar Supreme Council of Health advised in November 2013 that people with underlying health conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, respiratory disease, the immunosuppressed, and the elderly, avoid any close animal contacts when visiting farms and markets, and to practice good hygiene, such as washing hands.

A further study on dromedary camels from Saudi Arabia published in December 2013 revealed the presence of MERS-CoV in 90% of the evaluated dromedary camels (310), suggesting that dromedary camels not only could be the main reservoir of MERS-CoV, but also the animal source of MERS.[46]

According to the 27 March 2014 MERS-CoV summary update, recent studies support that camels serve as the primary source of the MERS-CoV infecting humans, while bats may be the ultimate reservoir of the virus. Evidence includes the frequency with which the virus has been found in camels to which human cases have been exposed, seriological data which shows widespread transmission in camels, and the similarity of the camel CoV to the human CoV.

On 6 June 2014, the Arab News

newspaper highlighted the latest research findings in the New England Journal of Medicine in which a 44-year-old Saudi man who kept a herd of nine camels died of MERS in November 2013. His friends said they witnessed him applying a topical medicine to the nose of one of his ill camels—four of them reportedly sick with nasal discharge—seven days before he himself became stricken with MERS. Researchers sequenced the virus found in one of the sick camels and the virus that killed the man, and found that their genomes were identical. In that same article, the Arab News reported that as of 6 June 2014, there have been 689 cases of MERS reported within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia with 283 deaths.

Transmission

Camels

A study performed between 2010 and 2013, in which the incidence of MERS was evaluated in 310 dromedary camels, revealed high titers of neutralizing antibodies to MERS-CoV in the blood serum of these animals. A further study sequenced MERS-CoV from nasal swabs of dromedary camels in Saudi Arabia and found they had sequences identical to previously sequenced human isolates. Some individual camels were also found to have more than one genomic variant in their nasopharynx.There is also a report of a Saudi Arabian man who became ill seven days after applying topical medicine to the noses of several sick camels and later he and one of the camels were found to have identical strains of MERS-CoV. It is still unclear how the virus is transmitted from camels to humans. The World Health Organization advises avoiding contact with camels and to eat only fully cooked camel meat, pasteurized camel milk, and to avoid drinking camel urine. Camel urine is considered a medicine for various illnesses in the Middle East.The Saudi Ministry of Agriculture has advised people to avoid contact with camels or wear breathing masks when around them.

In response "some people have refused to listen to the government's advice. and kiss their camels in defiance of their government's advice.

Between person

There has been evidence of limited, but not sustained spread of MERS-CoV from person to person, both in households as well as in health care settings like hospitals. Most transmission has occurred "in the circumstances of close contact with severely ill persons in healthcare or household settings" and there is no evidence of transmission from asymptomatic cases.Cluster sizes have ranged from 1 to 26 people, with an average of 2.7.

Evolution

The virus appears to have originated in bats. The virus itself has been isolated from a bat. Serological evidence shows that these viruses have infected camels for at least 20 years. The most recent common ancestor of several human strains has been dated to March 2012 (95% confidence interval December 2011 to June 2012).

This virus is closely related to the Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4 and Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5.

The evidence available to date suggests that the viruses have been present in bats for some time and had spread to camels by the mid 1990s. The viruses appear to have spread from camels to humans in the early 2010s. The original bat host species and the time of initial infection in this species has yet to be determined.

Virology

Middle East respiratory syndrome is caused by the newly identified MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV), a species with single-stranded RNAbelonging to the genus betacoronavirus which is distinct from SARS coronavirus and the common-cold coronavirus. Its genomes are phylogenetically classified into two clades, Clades A and B. Early cases of MERS were of Clade A clusters (EMC/2012 and Jordan-N3/2012) while new cases are genetically different in general (Clade B). The virus grows readily on Vero cells and LLC-MK2 cells

Signs and symptoms

Early reports compared the virus to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and it has been referred to as Saudi Arabia's SARS-like virus. The first person, in June 2012, had a "seven-day history of fever, cough, expectoration, and shortness of breath.One review of 47 laboratory confirmed cases in Saudi Arabia gave the most common presenting symptoms as fever in 98%, cough in 83%, shortness of breath in 72% and myalgia in 32% of people. There were also frequent gastrointestinal symptoms with diarrhea in 26%, vomiting in 21%, abdominal pain in 17% of people. 72% of people required mechanical ventilation. There were also 3.3 males for every female. One study of a hospital-based outbreak of MERS had an estimated incubation period of 5.5 days (95% confidence interval 1.9 to 14.7 days).

MERS can range from asymptomatic disease to severe pneumonia leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Kidney failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and pericarditis have also been reported

MERS can range from asymptomatic disease to severe pneumonia leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Kidney failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and pericarditis have also been reported

Middle East respiratory syndrome

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), also known as camel flu, is a viral respiratory infection caused by the MERS-corona virus (MERS-CoV). Symptoms may range from mild to severe. They include fever, cough, diarrhea, and shortness of breath.Disease is typically more severe in those with other health problems.

MERS-CoV is a beta corona virus derived from bats.Camels have been shown to have antibodies to MERS-CoV but the exact source of infection in camels has not been identified. Camels are believed to be involved in its spread to humans but it is unclear how.Spread between humans typically requires close contact with an infected person. Its spread is uncommon outside of hospitals. Thus its risk to the globally population is deemed to be currently fairly low.

As of 2015 there is no specific vaccine or treatment for the disease.However, a number of antiviral medications are currently being studied. The World Health Organization recommends that those who come in contact with camels wash their hands frequently and do not touch sick camels. They also recommend that camel products be appropriately cooked. Among those who are infected treatments that help with the symptoms may be given.

Just over 1000 cases of the disease have been reported as of May 2015.About 40% of those who become infected die from the disease.The first identified case occurred in 2012 in Saudi Arabia and most cases have occurred in the Arabian Peninsula.A strain of MERS-CoV known as HCoV-EMC/2012 found in the first infected person in London in 2012 was found to have a 100% match to Egyptian tomb bats. A large outbreak occurred in the Republic of Korea in 2015.

Cultural effects of the Ebola crisis

The Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa has had a large effect on the culture of most of the West African countries. In most instances, the effect is a rather negative one as it has disrupted many Africans’ traditional norms and practices. For instance, many West African communities rely on traditional healers and witch doctors, who use herbal remedies, massage, chant, and witchcraft to cure just about any ailment.Therefore, it is difficult for West Africans to adapt to foreign medical practices. Specifically, West African resistance to Western medicine is prominent in the region, which calls for severe distrust of Western and modern medical personnel and practices.

Similarly, some African cultures have a traditional solidarity of standing by the sick, which is contrary to the safe care of an Ebola patient.This tradition is known as "standing by the ill" in order to show one's respect and honor to the patient. According to the Wesley Medical Center, these sorts of traditional norms can be dangerous to those not infected with the virus as it increases their chances of coming in contract with their family member's bodily fluids.In Liberia, Ebola has wiped out entire families, leaving perhaps one survivor to recount stories of how they simply could not be hands off while their loved ones were sick in bed, because of their culture of touch, hold, hug and kiss.

Some communities traditionally use folklore and mythical literature, which is often passed on verbally from one generation to the next to explain the interrelationships of all things that exist. However the folklore and songs are not only of traditional or ancient historical origins, but are often about current events that have affected the community. Additionally, folklore and music will often take opposing sides of any story. Thus early in the Ebola epidemic, the song "White Ebola" was released by a diaspora based group and centers on the general distrust of "outsiders" who may be intentionally infecting people.

This initial misinformation increased the general distrust in foreigners, and the idea that Ebola was not in Africa before their arrival led to attacks on many health workers as well as blockages of aid convoys blocked from checking remote areas. A burial team, which was sent in to collect the bodies of suspected Ebola victims from West Point in Liberia, was blocked by several hundred residents chanting: "No Ebola in West Point." Health ministries and workers started an aggressive Ebola information campaign on all media formats to properly inform the residents and allow aid workers safe access to the high risk areas In Guinea, riots broke out after medics disinfected a market in Nzerekore. Locals rumored that the medics were actually spreading the disease. In nearby Womey, 8 people distributing information about Ebola were killed by the villagers.

Infectin control

People who care for those infected with Ebola should wear protective clothing including masks, gloves, gowns and goggles. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommend that the protective gear leaves no skin exposed.These measures are also recommended for those who may handle objects contaminated by an infected person's body fluids. In 2014, the CDC began recommending that medical personnel receive training on the proper suit-up and removal of personal protective equipment (PPE); in addition, a designated person, appropriately trained in biosafety, should be watching each step of these procedures to ensure they are done correctly. In Sierra Leone, the typical training period for the use of such safety equipment lasts approximately 12 days.

The infected person should be in barrier-isolation from other people.All equipment, medical waste, patient waste and surfaces that may have come into contact with body fluids need to be disinfected. During the 2014 outbreak, kits were put together to help families treat Ebola disease in their homes, which include protective clothing as well as chlorine powder and other cleaning supplies. Education of those who provide care in these techniques, and the provision of such barrier-separation supplies has been a priority of Doctors Without Borders.

Ebolaviruses can be eliminated with heat (heating for 30 to 60 minutes at 60 °C or boiling for 5 minutes). To disinfect surfaces, some lipid solvents such as some alcohol-based products, detergents, sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or calcium hypochlorite (bleaching powder), and other suitable disinfectants may be used at appropriate concentrations. Education of the general public about the risk factors for Ebola infection and of the protective measures individuals may take to prevent infection is recommended by the World Health Organization.These measures include avoiding direct contact with infected people and regular hand washing using soap and water.

Bushmeat, an important source of protein in the diet of some Africans, should be handled and prepared with appropriate protective clothing and thoroughly cooked before consumption. Some research suggests that an outbreak of Ebola disease in the wild animals used for consumption may result in a corresponding human outbreak. Since 2003, such animal outbreaks have been monitored to predict and prevent Ebola outbreaks in humans.

If a person with Ebola disease dies, direct contact with the body should be avoided. Certain burial rituals, which may have included making various direct contacts with a dead body, require reformulation such that they consistently maintain a proper protective barrier between the dead body and the living. Social anthropologists may help find alternatives to traditional rules for burials.

Transportation crews are instructed to follow a certain isolation procedure should anyone exhibit symptoms resembling EVD.As of August 2014, the WHO does not consider travel bans to be useful in decreasing spread of the disease. In October 2014, the CDC defined four risk levels used to determine the level of 21-day monitoring for symptoms and restrictions on public activities.In the United States, the CDC recommends that restrictions on public activity, including travel restrictions, are not required for the following defined risk levels:

- having been in a country with widespread Ebola disease transmission and having no known exposure (low risk); or having been in that country more than 21 days ago (no risk)

- encounter with a person showing symptoms; but not within 3 feet of the person with Ebola without wearing PPE; and no direct contact of body fluids

- having had brief skin contact with a person showing symptoms of Ebola disease when the person was believed to be not very contagious (low risk)

- in countries without widespread Ebola disease transmission: direct contact with a person showing symptoms of the disease while wearing PPE (low risk)

- contact with a person with Ebola disease before the person was showing symptoms (no risk).

The CDC recommends monitoring for the symptoms of Ebola disease for those both at "low risk" and at higher risk.

In laboratories where diagnostic testing is carried out, biosafety level 4-equivalent containment is required. Laboratory researchers must be properly trained in BSL-4 practices and wear proper PPE

Immune system evasion

Filoviral infection also interferes with proper functioning of the innate immune system. EBOV proteins blunt the human immune system's response to viral infections by interfering with the cells' ability to produce and respond to interferon proteins such as interferon-alpha, interferon-beta, and interferon gamma.

The VP24 and VP35 structural proteins of EBOV play a key role in this interference. When a cell is infected with EBOV, receptors located in the cell's cytosol (such as RIG-I andMDA5Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9), recognize infectious molecules associated with the virus. On TLR activation, proteins including interferon regulatory factor 3 and interferon regulatory factor 7 trigger a signaling cascade that leads to the expression of type 1 interferons. The type 1 interferons are then released and bind to the IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 receptors expressed on the surface of a neighboring cell. Once interferon has bound to its receptors on the neighboring cell, the signaling proteins STAT1 and STAT2 are activated and move to the cell's nucleusThis triggers the expression of interferon-stimulated genes, which code for proteins with antiviral properties. EBOV's V24 protein blocks the production of these antiviral proteins by preventing the STAT1 signaling protein in the neighboring cell from entering the nucleus. The VP35 protein directly inhibits the production of interferon-beta. By inhibiting these immune responses, EBOV may quickly spread throughout the body

Virology

Ebolaviruses contain single-stranded, non-infectious RNA genomes. Ebolavirus genomes contain seven genes including UTR-NP-VP35-VP40-GP-VP30-VP24-L-5'-UTR The genomes of the five different ebolaviruses (BDBV, EBOV, RESTV, SUDV and TAFV) differ in sequence and the number and location of gene overlaps. As with all filoviruses, ebolavirus virions are filamentous particles that may appear in the shape of a shepherd's crook, of a "U" or of a "6," and they may be coiled, toroid or branched.In general, ebolavirions are 80 nanometers (nm) in width and may be as long as 14,000 nm.

Their life cycle is thought to begin with a virion attaching to specific cell-surface receptors such as C-type lectins, DC-SIGN, or integrins, which is followed by fusion of the viral envelope with cellular membranes. The virions taken up by the cell then travel to acid icendosomes and lysosomes where the viral envelope glycoprotein GP is cleaved.[34] This processing appears to allow the virus to bind to cellular proteins enabling it to fuse with internal cellular membranes and release the viral nucleocapsid. The Ebolavirus structural glycoprotein (known as GP1,2) is responsible for the virus' ability to bind to and infect targeted cells. The viral RNA polymerase, encoded by the L gene, partially uncoats the nucleocapsid and transcribes the genes into positive-strand mRNAs, which are then translated into structural and nonstructural proteins. The most abundant protein produced is the nucleoprotein, whose concentration in the host cell determines when L switches from gene transcription to genome replication. Replication of the viral genome results in full-length, positive-strand antigenomes that are, in turn, transcribed into genome copies of negative-strand virus progeny. Newly synthesized structural proteins and genomes self-assemble and accumulate near the inside of the cell membrane. Virions bud off from the cell, gaining their envelopes from the cellular membrane from which they bud from. The mature progeny particles then infect other cells to repeat the cycle. The genetics of the Ebola virus are difficult to study because of EBOV's virulent characteristics.

Recovery and death

Recovery may begin between 7 and 14 days after first symptoms. Death, if it occurs, follows typically 6 to 16 days from first symptoms and is often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss. In general, bleeding often indicates a worse outcome, and blood loss may result in death. People are often in a coma near the end of life.

Those who survive often have ongoing muscular and joint pain, liver inflammation, decreased hearing, and may have continued feelings of tiredness, continued weakness, decreased appetite, and difficulty returning to pre-illness weight. Problems with vision may develop.

Additionally they develop antibodies against Ebola that last at least 10 years, but it is unclear if they are immune to repeated infections.] If someone recovers from Ebola, they can no longer transmit the disease

Bleeding

In some cases, internal and external bleeding may occur.This typically begins five to seven days after the first symptoms. All infected people show some decreased blood clotting. Bleeding from mucous membranes or from sites of needle punctures has been reported in 40–50 percent of cases.vomiting blood, coughing up of blood, or blood in stool. Bleeding into the skin may create petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses or hematomas (especially around needle injection sites). Bleeding into the whites of the eyes may also occur. Heavy bleeding is uncommon; if it occurs, it is usually located within the gastrointestinal tract.

This may cause

Onset

The length of time between exposure to the virus and the development of symptoms (incubation period) is between 2 to 21 days, and usually between 4 to 10 days.However, recent estimates based on mathematical models predict that around 5% of cases may take greater than 21 days to develop.

Symptoms usually begin with a sudden influenza-like stage characterized by feeling tired, fever, weakness, decreased appetite, muscular pain, joint pain, headache, and sore throat. The fever is usually higher than 38.3 °C (101 °F). This is often followed by vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain. Next, shortness of breath and chest pain may occur, along with swelling, headaches andconfusion. In about half of the cases, the skin may develop a maculopapular

ash, a flat red area covered with small bumps, 5 to 7 days after symptoms begin.

Ebola virus disease

Ebola virus disease (EVD; also Ebola hemorrhagic fever, or EHF), or simply Ebola, is a disease of humans and other primates caused by ebola viruses. Signs and symptoms typically start between two days and three weeks after contracting the virus with a fever, sore throat, muscular pain, and headaches. Then, vomiting, diarrhea and rash usually follow, along with decreased function of the liver and kidneys. At this time some people begin to bleed both internally and externally. The disease has a high risk of death, killing between 25 and 90 percent of those infected, with an average of about 50 percent. This is often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss, and typically follows six to sixteen days after symptoms appear.

The virus spreads by direct contact with body fluids, such as blood, of an infected human or other animals.This may also occur through contact with an item recently contaminated with bodily fluids. Spread of the disease through the air between primates, including humans, has not been documented in either laboratory or natural conditions. Semen or breast milk of a person after recovery from EVD may still carry the virus for several weeks to months. Fruit bats are believed to be the normal carrier in nature, able to spread the virus without being affected by it. Other diseases such as malaria, cholera, typhoid fever, meningitis and other viral hemorrhagic fevers may resemble EVD. Blood samples are tested for viral RNA, viral antibodies or for the virus itself to confirm the diagnosis.

Control of outbreaks requires coordinated medical services, alongside a certain level of community engagement. The medical services include rapid detection of cases of disease, contact tracing of those who have come into contact with infected individuals, quick access to laboratory services, proper healthcare for those who are infected, and proper disposal of the dead through crrmation the special caution. Prevention includes limiting the spread of disease from infected animals to humans. This may be done by handling potentially infected bush meat only while wearing protective clothing and by thoroughly cooking it before eating it. It also includes wearing proper protective clothing and washing hands when around a person with the disease.No specific treatment or vaccine for the virus is available, although a number of potential treatments are being studied. Supportive efforts, intravenous fluids as well as treating symptoms.

however, improve outcomes. This includes either oral rehydration therapy (drinking slightly sweetened and salty water) or giving

The disease was first identified in 1976 in two simultaneous outbreaks, one in Nzara, and the other in Yambuku, a village near the Ebola River from which the disease takes its name. EVD outbreaks occur intermittently in tropical regions of sub-Saharan Africa.Between 1976 and 2013, the World Health Organization reports a total of 24 outbreaks involving 1,716 cases.[ The largest outbreak is the ongoing epidemic in West Africa, still affecting Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. As of 30 August 2015, this outbreak has 28,109 reported cases resulting in 11,305 deaths.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)